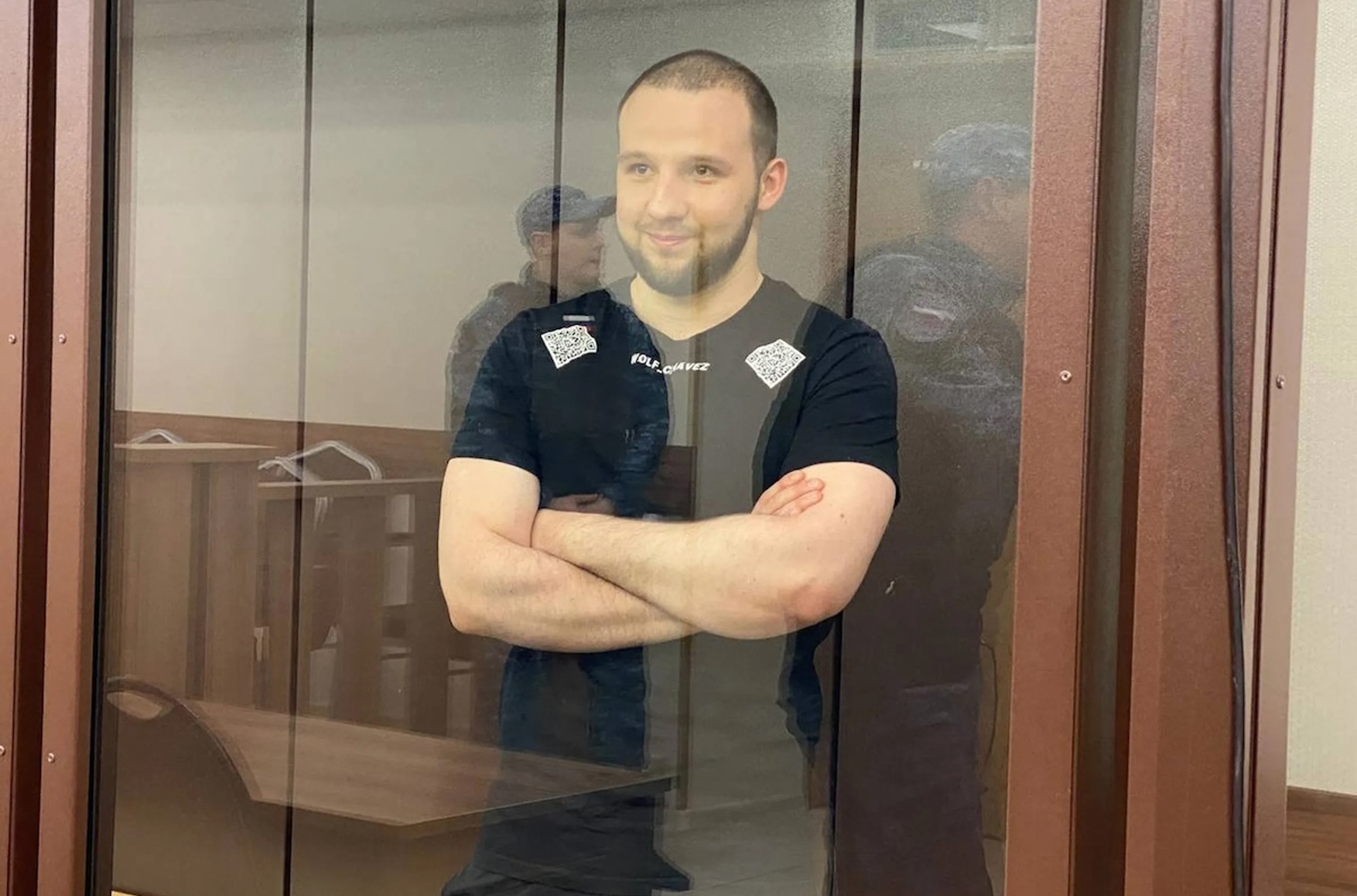

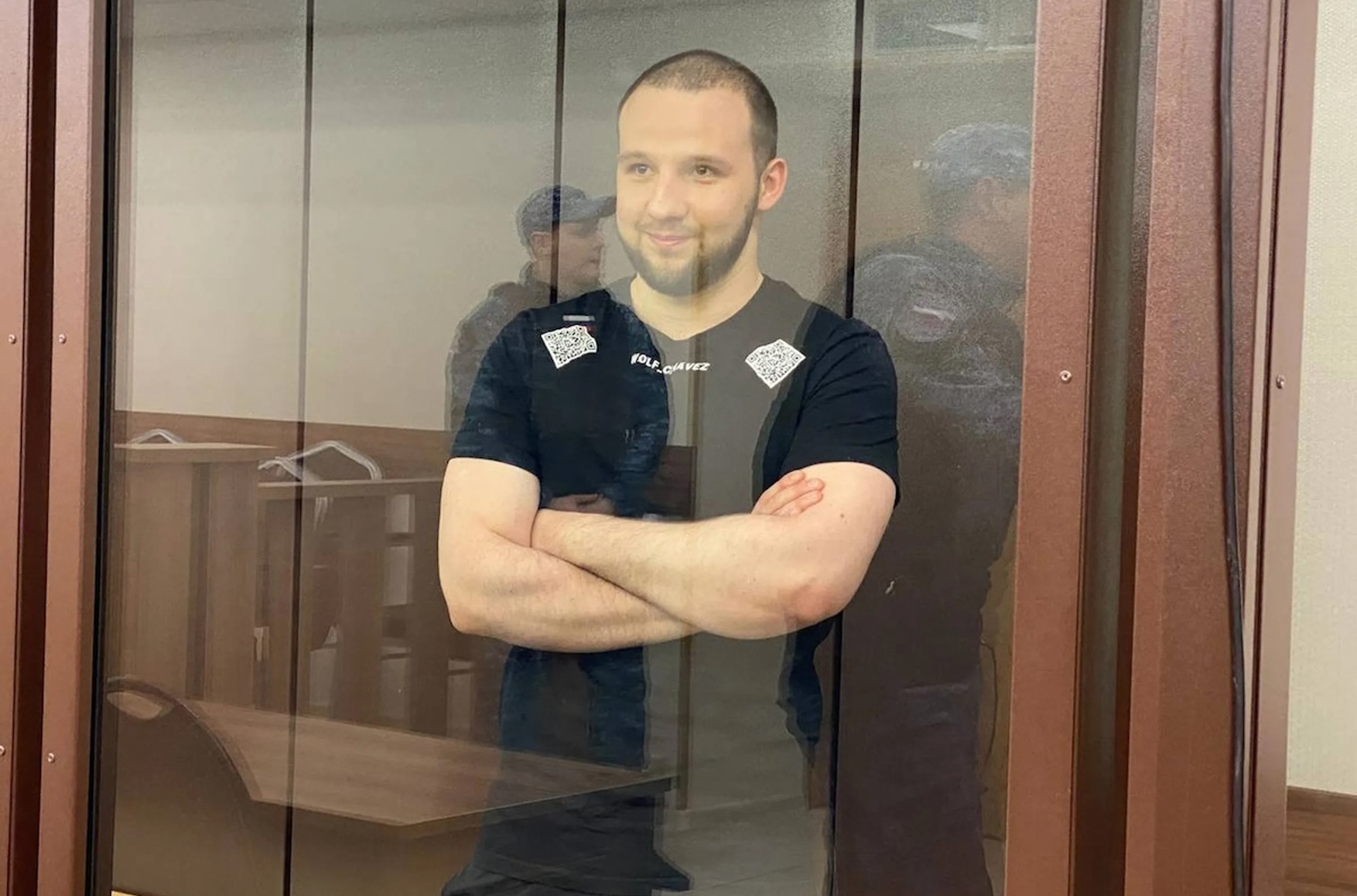

Between February 2022 and January 2025, at least 280 arson attacks targeting enlistment offices and other military or administrative facilities were recorded in Russia. However, an unknown number of these incidents were carried out by the FSB itself, with the targets of law enforcement receiving lengthy prison sentences for playing a minor role in the overall plot. On May 20, 2025, Novosibirsk resident Ilya Baburin was handed 25 years in prison for making plans to set fire to a military enlistment office. In reality, there was no arson — and no serious preparations to commit one. Instead, state law enforcement agents staged a mock enlistment office, set it on fire themselves, and filmed the “arson attack.” Before that, they had already recruited two of Baburin’s acquaintances in order to create a link between the “perpetrator” and the “crime.” Using materials from Baburin’s criminal case, The Insider can explain how such acts of entrapment are constructed.

Content

“I had to see it through”: building the storyline

Narzan and an iPhone: delivering the props

The “undercover operation”: staging the arson

An unused phone, an unrecorded conversation: collecting “evidence”

Gas cans, a book, and a GPS tracker: new “evidence”

Recruited by Azov: the investigation’s version

25 years for talk of arson: the verdict

“I had to see it through”: building the storyline

On September 9, 2022, 22-year-old Novosibirsk resident Ilya Baburin messaged his friend Timofey Orlov [names taken from the case files — The Insider] with an offer to earn some money. Without sharing any extra details, Orlov immediately forwarded the message to an acquaintance of his, Dmitry Shorin. The next day, all three met in person.

At their meeting near the Galereya shopping mall in the city center, Baburin offered Shorin 30,000 rubles ($380) to carry out a task: set fire to a military enlistment office by throwing a Molotov cocktail at it. Shorin didn’t have to do it himself — the main thing was to film the act. According to Shorin, the video was supposed to be sent “to some friends in Azov.” This mention of the Ukrainian battalion, which is designated as a terrorist organization in Russia, would later result in much harsher charges against Baburin.

At the time, Shorin was under a travel ban — he was under criminal investigation and facing serious jail time. He later told the court that Baburin had promised to help him get to Ukraine. Shorin accepted Baburin’s offer, although he admitted he “knew he wasn’t actually going to go through with it.”

The September 10 meeting outside Galereya was Shorin’s first and last in-person encounter with Baburin. On September 11, he went to the FSB regional office in Novosibirsk and reported the proposal, agreeing to take part in an “operational experiment.” Later, in court, Shorin explained: “They needed to find out how the arson was going to be carried out.” That’s how the security services launched their “operation” against Baburin — on charges of “organizing a terrorist attack.”

Shorin told the FSB he had been approached with a proposal to set fire to a military enlistment office

Shorin was instructed to contact Orlov and persuade him to arrange another meeting with Baburin — ostensibly in order to discuss the details of the arson. However, it turned out that Baburin had already abandoned the idea. Orlov later confirmed this in his testimony: “After the meeting, Ilya [Baburin] said there was no need to do anything. The operation was called off.”

Despite Baburin’s lack of interest, Shorin continued to push for the meeting. “I had to see it through,” he would later tell the court. At this point, the “operation” against Baburin turned into entrapment, with the initiative no longer coming from the supposed “organizer,” but from the security officers, who had a vested interest in staging a “terror plot” in order to then “solve” the crime.

“Entrapment is when a public official or their agent induces someone to commit a crime,” explains human rights lawyer Dmitry Zakhvatov. “That is, when a person is persuaded, pressured, or drawn into something they wouldn't have done on their own. In political cases, this often happens through fake Telegram bots supposedly operated by Ukrainian intelligence. People start chatting, thinking they’re communicating with the Ukrainian side, but in fact it’s an operative who systematically steers them toward a point where criminal charges can be made. Then they’re arrested.”

Zakhvatov emphasizes that a lawful undercover operation works differently:

“It may involve surveillance, information gathering, wiretapping, or infiltration of certain circles — but without directly encouraging a person to commit a crime. The officer documents what’s happening but doesn’t push the person into action.”

Another lawyer, who spoke to The Insider on condition of anonymity, explained that the difference between an undercover operation and an example of entrapment lies in the fact that in the latter, the target is actively drawn into a criminal act by a law enforcement officer:

“A lawful undercover operation simulates a possible offense: if the person voluntarily engages in illegal actions, they are detained. It’s like a trap they walk into on their own. Entrapment, on the other hand, is when someone is pushed toward committing a crime against their will. This can involve trickery, psychological pressure, manipulation. In practice, the line between the two is thin — but the key principle is voluntariness.”

Narzan and an iPhone: delivering the props

After a few days of repeated urging from Orlov and Shorin, Baburin finally agreed to meet with Orlov, but not with Shorin. On September 20, he handed Orlov a bottle labeled Narzan filled with a flammable liquid, along with an iPhone 6 meant to record the arson.

That same day, Orlov met Shorin near a café close to Galereya and handed over the bottle and phone. The exchange took place under FSB surveillance. After receiving the “tools of the crime,” Shorin immediately turned them over to law enforcement officers.

After his meeting with Shorin, Orlov himself went to the regional FSB office. According to case materials, he claimed he feared the consequences of his actions and agreed to take part in an “operational investigative activity.”

Neither Orlov nor Shorin knew that the FSB had recruited both of them. Only the security service was aware of the full setup.

The “undercover operation”: staging the arson

By the time Dmitry Shorin delivered the bottle and smartphone to the FSB, the script for the “arson” was already complete. Only the climax remained. FSB officer Igor Fintisov took charge of staging the event.

The operative found an abandoned building in Novosibirsk and prepared the “set,” mounting a sign on the facade identifying it as a military enlistment office. Then, under “controlled conditions,” he carried out the arson himself, filming it as directed.

The FSB officer found an abandoned building and prepared the “set” by affixing a sign identifying the structure as a military enlistment office

Fintisov did not specify who exactly carried out the arson, but in his testimony he directly confirmed it was an FSB operation. The security service had “…organized the arson of an abandoned building, to the facade of which a sign from one of Novosibirsk’s military enlistment offices had been attached in advance.”

An unused phone, an unrecorded conversation: collecting “evidence”

According to Fintisov’s plan, Shorin was supposed to pass the phone with the recorded video to Baburin through Orlov. This would allow investigators to establish a connection between the supposed “perpetrator” and the “organizer.” But it turned out there was no need to return the phone, as “Baburin told Orlov that returning the mobile phone wasn’t necessary. The recorded video was to be sent via Telegram to an account created specifically for that purpose…”

The conversation was being recorded, but when the evidence was supposed to be handed over to investigators, the audio file was mysteriously missing:

“The audio recording of the conversation between Orlov and Baburin, obtained using a special technical device, was damaged during transfer to a computer drive and could not be presented to the investigator.”

The loss of the recording likely worked in the FSB’s favor, as the authentic conversation could have confirmed that Baburin had abandoned the idea and was trying to distance himself from the plot. The handoff of the phone to Baburin was supposed to be the final act in the FSB’s carefully constructed operation, but his refusal to take the “evidence” derailed those plans.

The security service soon learned that Baburin had purchased a plane ticket to Moscow for September 22. Investigators claimed he intended to flee and detained him at the airport. His home was searched. On September 23, a court ordered Baburin into pre-trial detention on charges of “attempted organization of a terrorist act.” The bottle, the iPhone 6, and the video of the burning abandoned building were entered into the case file as “evidence of terrorist activity.”

Dmitry Zakhvatov points out that Baburin’s case clearly involved an element of entrapment — the supposed “perpetrators,” following FSB instructions, persuaded him to return to the idea of arson:

“Even if someone at some point planned something but then consciously backed out, that should matter. Under the law, there should be no consequences in such cases. Here, as we can see, it was the officers themselves who initiated further contact. That’s what makes the charge unlawful: prosecuting a person for actions they were deliberately pushed toward — that’s the very definition of entrapment.”

Another lawyer, who requested anonymity, notes that it is possible to defend oneself against being entrapped by issuing a clearly worded and documented refusal:

“Russian criminal law includes the concept of voluntary renunciation. If a person consciously withdraws before the crime is committed, they are not subject to criminal liability. To protect oneself, a person needs to express an unequivocal refusal. Ideally, in writing. Say to the person: ‘I’m not interested, I don’t intend to be involved’ — and save the message. That alone may be enough.”

Gas cans, a book, and a GPS tracker: new “evidence”

At Baburin’s home, officers hunted for anything that might support the charge of “organizing a terrorist act.” Investigators documented two jerry cans of transmission oil, the box from an iPhone 6, some flashbang cartridges, and a copy of William Shirer’s The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich.

All of these items were added to the list of evidence supposedly showing Baburin’s preparation for arson: the oil, investigators claimed, could be used to make an incendiary mixture, and the serial number on the box matched that of the phone that Shorin had handed over to the operatives.

As for the book, it was cited by investigators as evidence of Baburin’s “neo-Nazism” and his alleged links to “Azov,” which Shorin had mentioned in his testimony. In the case file, the book is described as “a manual on Nazi ideology,” although in reality it is one of the most well-known historical works on Nazi Germany and is freely available for purchase in Russia.

The book — a historical study of Germany during World War II — was treated by investigators as a “manual on Nazi ideology”

In addition, a GPS tracker found at Baburin’s home was later used as evidence in yet another criminal case against him. By the time the search occurred, the FSB had already finished the staging of the “terror attack.” Now its focus shifted to constructing the image of Baburin as its “mastermind.”

Recruited by Azov: the investigation’s version

According to the security services, Ilya Baburin was the “organizer of the terrorist attack” and had been recruited by the Azov Battalion. In 2021, he spent several months in Ukraine, where his wife — from whom he had separated by the time of his arrest — was living. The FSB claims it was during his time in Ukraine that Baburin “established ties” with members of the battalion — and even considered joining it himself.

After Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Baburin’s supposed Azov contacts allegedly offered him money in exchange for “assisting” them. It was out of this supposed desire to “help” that Baburin, according to the FSB, decided to carry out arson attacks in Russia and distribute videos of the acts online.

However, as Baburin’s lawyer Vasily Dubkov emphasized, investigators had no direct evidence that his client had been recruited. Yet the subsequent charges against him were built entirely on this assumption.

Most of the charges brought against Baburin were based on his alleged ties to Azov

In March 2023, due to these supposed connections, Baburin was even charged with “treason,” which consisted of “aiding the battalion in actions against Russia” — specifically, in “organizing” the failed arson attempt. Then in September 2023, one year after Baburin’s arrest in the case of the staged “arson,” FSB investigator Georgy Golovachev charged him with “terrorism” and “illegal possession of surveillance equipment.”

The “terrorist act” was identified as the July 1, 2022 arson of a children's music school in Novosibirsk. The prosecution’s main piece of evidence linking Baburin to this episode was a video found on his phone. The video showed a burning building that resembled a school. However, investigators were unable to prove that Baburin had filmed the video himself.

Experts for the prosecution could only confirm that the footage had been recorded on a phone of the same model Baburin owned — an iPhone 12 Pro Max. They explicitly stated they had not been tasked with determining where, when, or on which specific device the file was created. Baburin maintained that he had not filmed the video and had no involvement in the arson.

The charge of “illegal possession of surveillance equipment” stemmed from Baburin’s purchase of the previously mentioned GPS tracker found during the search. It turned out the device had a built-in microphone. During questioning, Baburin explained that he had bought the tracker from an online marketplace out of curiosity and had no idea it contained a mic: “I didn’t even activate it. It was just a Chinese gadget. I thought I’d use it as a GPS tracker for the car I used to have.”

Finally, in December, investigators concluded that Baburin was not merely helping Azov but was a member of the group. He was charged with participating in an “illegal armed formation” and a “terrorist organization” — charges based entirely on the arson episodes from July and September 2022.

A year and a half after Baburin’s arrest, investigators concluded that he was not merely assisting Azov, but was an actual member of the group

The foundation for these charges was the testimony of Shorin, who appeared in court as a secret witness, participating in the hearings from a separate room, with his voice altered. In the case file, Shorin was identified by a pseudonym, while his real identity, according to the court documents, was “kept in a sealed envelope.”

Shorin claimed that during their September 2022 meeting, Baburin had insisted on filming the “arson of the military enlistment office.” The video, he said, was needed “to intimidate the population” and “incite protest against the special military operation,” as well as to prove his own readiness for “more serious and better-paid” assignments from Azov. No supporting evidence for these allegations was presented — only the distorted voice of the anonymous witness.

25 years for talk of arson: the verdict

On May 20, 2024, the Second Eastern District Military Court in Novosibirsk sentenced Ilya Baburin to 25 years of imprisonment. According to the ruling, five of those years are to be served in prison, with the remaining twenty in a maximum-security penal colony.

In his final statement to the court, Ilya Baburin argued that both Orlov and “Shorin,” the key witnesses whose testimony formed the basis of the charges against him, had acted under pressure from the FSB:

“One of them had a case open for kidnapping and was under a travel ban. He was about to be convicted. That was the person who played the role of the perpetrator. But he decided to make things easier for himself by turning me in — and it worked. According to the FSB officers, they got his Interior Ministry investigator replaced, found him a job, and made sure he wouldn’t serve time. Everything worked out for him. The second witness is the one who introduced me to the first. They told him to testify against me, or else he would be charged instead of me under the same statutes.”

Baburin also stressed that he had explicitly refused to go through with the arson plan, but “Shorin” had received orders from security officers to persuade him to reconsider:

“What’s most interesting in this case is that I told the witness not to do anything, that everything was off. At that point, he was already cooperating with the FSB. During the trial, my lawyer asked the witness whether FSB officers had given him any instructions after I canceled the plan. The witness said no. But in the case materials, it’s written in plain language that officers gave him explicit instructions to pressure me. Of course it wasn’t in their interest for the crime not to happen. And the witness had no interest either — if I didn’t get sentenced, no one would cut him a deal.”

Lawyer Vasily Dubkov emphasized that all the evidence in the case was circumstantial. Baburin was not present at the site of the arson, did not attend any meetings, and did not film any videos. All key actions by the “perpetrators” took place under FSB supervision. Moreover, all testimonies came from individuals who had personal motivations for cooperating with the investigators. The court dismissed these arguments.

“What I intended to do was hooliganism — or more precisely, attempted hooliganism. I did not set anything on fire. Given the current situation, FSB officers are being offered chances to earn promotions and advance their careers by uncovering fabricated crimes. Why open cases for attempted property damage or hooliganism when you can charge someone with terrorism and treason? They stand to gain more that way. Whether a person ends up spending twenty or thirty years in prison because of their twisted ambitions is of little concern to them.”

Human rights lawyer Dmitry Zakhvatov noted that there has never been an instance in Russian judicial practice when charges were dropped due to entrapment by security forces:

“There is no real court in Russia. We have a judicial system but no judicial authority. Judges do not make decisions; they simply echo the prosecution’s case. I do not know of a single instance where a lawyer has successfully challenged charges based on operational entrapment. Even when the entrapment is obvious, it doesn’t work.”

The anonymous lawyer told The Insider that, to conceal entrapment, security officers may coerce the accused into pleading guilty in exchange for a reduced sentence, or by classifying case materials demonstrating officer misconduct:

“Even if the entrapment is clear, defendants are often forced to admit guilt and accept plea deals to receive lighter sentences. They simply have no other choice. Another tactic is to classify materials that could prove the entrapment. The document receives a ‘top secret’ stamp, and nothing can be done with it. The lawyer cannot even publicly reference it, because mentioning it turns the hearing into a closed session.”

In March 2025, the human rights organization Memorial officially recognized Ilya Baburin as a political prisoner.